On This Page:

Feedlot System Overview

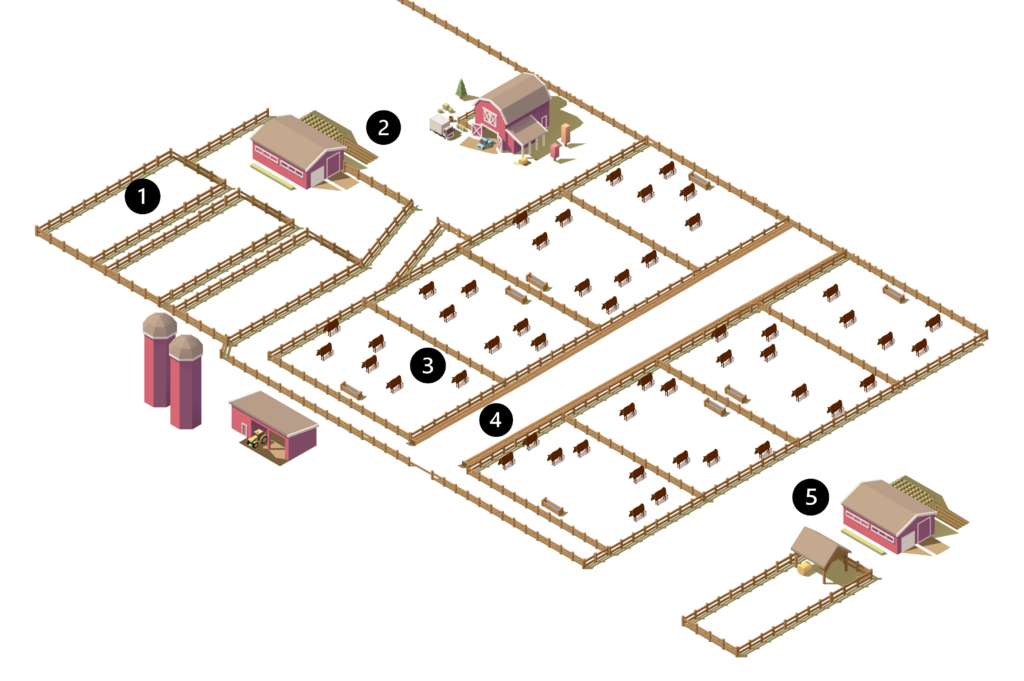

❶ Upon Arrival

Animals arriving at the feedlot are placed into different risk categories based on their known (or unknown) history. The categories (low, medium, high, and ultra-high risk) are determined by:

- Weight

- Sex

- Age

- Origin (i.e., direct from ranch vs. from auction)

- Recent stressors (i.e., weaning, sale, and transport experience)

- Medical history (i.e. vaccination schedule, history of illness and/or antibiotic treatments)

The cattle are offloaded from the transport vehicle and placed in holding pens before they can be processed. They are provided with fresh water and familiar feed. Handlers encourage the animals to eat and drink by literally leading them to the food and water if the calves aren’t familiar with eating on their own out of a bunk. Ensuring the animals eat and drink is essential to maintaining their health. If they don’t eat or drink, their health will decline very quickly. The cattle are processed immediately after arrival in order to get them homed and rested as soon as possible.

❷ Intake Process

Cattle are guided single-file through a curved chute and into an individual compartment called a “squeeze chute”. This squeeze chute gently squeezes and contains the animal to promote efficient handling and the safety of both the animal and the operator.

The animal is in the squeeze chute for at least thirty seconds, during which time the operator can perform the following actions:

- Use a Bluetooth wand to scan the animal’s permanent CCID RFID tag, which pulls up the animal’s profile on a nearby computer.

- Remove the previous owner’s plastic identification tag from the cattle’s ear. (The CCID RFID tag is not removed; it legally must stay with the animal.)

- Attach new plastic ear tags for identification: one to identify the individual animal, and one to identify the animal’s home pen.

- Application of an anti-parasitic.

- Administration of vaccinations if the animal is not fully vaccinated, or if vaccination status is unknown.

- Administration of prophylactic (preventative) antibiotics if necessary, as determined by the animal’s risk category.

- Depending on the marketing plan, animal age, and animal type, a growth hormone may be administered to improve feed efficiency.

The animal is then released from the squeeze chute and free to rejoin its fellows in another holding pen. When all of the animals are processed they are moved to their home pen.

❸ Home Pen

The cattle will eat, sleep and relax in their home pen for their entire stay at the feedlot unless they need to be “pulled” for treatment of an illness or injury. The horseback cowboy will not literally pull or rope the animal, but will gently encourage or ease the sick animal from their home pen, usually without the use of ropes or restraints, and bring them to a “hospital pen”.

In order to minimize the risk of transmitting illnesses, the pens with the highest risk animals (newly weaned calves) are separated from each other by pens of older, more resilient cattle.

The home pens are generally quiet, peaceful places where the cattle socialize with each other and often lay down to chew their cud between mealtimes.

Pen-Checking Cowboys

Cowboys ride through every pen at least once a day to check that the cattle are happy and healthy. If an animal displays any signs of illness, the cowboy will “pull” the animal from the pen and bring it to an isolated “hospital pen” to diagnose the issue.

“Pulling” the animal doesn’t mean physically pulling it from the pen, but rather the cowboy will encourage or ease the sick animal from the pen without using a rope or other restraint.

Cattle are prey animals, which means they need to be skilled at concealing illness or weakness so that predators don’t target them. It takes skilled cowboys or “pen-checkers” to get to know their animals and be able to recognize when a change in behaviour might indicate that something is wrong. Two of the best times to check for concerning behaviours are first thing in the morning, for instance if an animal is slow to get up and get moving, and at feeding time, if the animal is not eating.

As a rule of thumb, a skilled cowboy will be responsible for around 8,500 low risk cattle in a day, or about 5,000 high risk cattle. Unfortunately, skilled cowboys are not as plentiful as they once were. Emerging technologies can help reduce the burden on skilled pen-checkers by using animal movement trends or facial recognition to help diagnose potential illness, leaving the skilled pen-checkers more time to monitor high-risk pens where early detection of more subtle signs of illness can help prevent a large outbreak.

❹ Nutrition and Feed

Cattle feed is carefully formulated to offer the best nutrition at each stage of growth. “Backgrounding” is the term used for early growth and development, in which cost-effective, lower energy feed is provided to help the animal grow bigger while avoiding excess fat deposition. “Finishing” feed is higher energy and is best used near the end of the animals life because it adds weight more quickly.

As herd animals, cattle develop a social hierarchy or “pecking order” that defines which animals are dominant over the others. Once this order is established, the herd society operates peacefully and predictably. Because of this, each animal generally claims a unique position at the feeding bunk, and will return to this exact location at every feeding time. This means that it is important to ensure that the entire feed bunk is regularly cleaned and filled uniformly with fresh feed. The animals will not necessarily shift down the line to find food if there are gaps in feed distribution along the feed bunk, since this could disrupt their social hierarchy.

Instead of being provided with food 24 hours a day, the animals are fed two to three times a day, and these feed times are kept constant. This promotes appetite stimulation, and the arrival of the food truck is always an exciting event.

❺ Treatment Facility/Animal Hospital

Animals exhibiting signs of illness (low energy, lack of eating or drinking, coughing, runny nose, etc.) are pulled from their home pen and moved to a hospital pen. Depending on their symptoms, they may be simply monitored, or they may be treated for an illness according to a veterinary prescribed treatment protocol. Rectal thermometers are used to verify that the animal has a fever prior to treatment.

Feedlots have close working relationships with veterinarians, who advise on treatment protocols and can prescribe drugs, including antimicrobials, to help the animal recover. Quarterly reviews are held with the veterinarians to assess health issues and adjust vaccination/treatment protocols for the future.

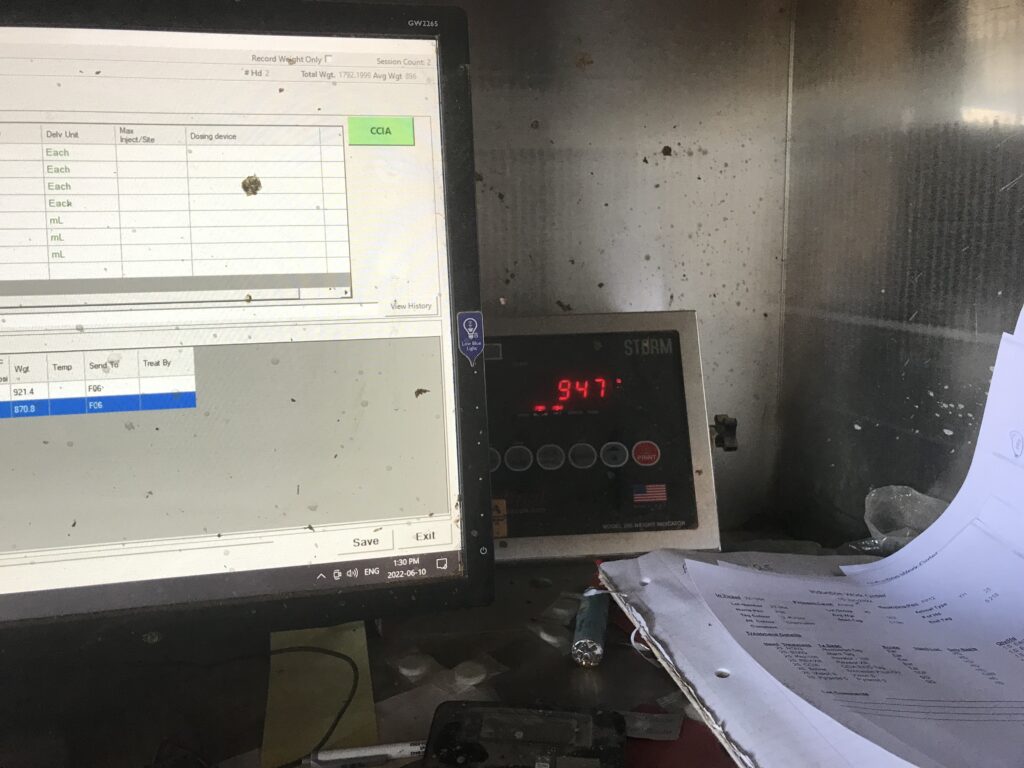

Administration of products, both upon arrival at the feedlot and at a treatment event, is based on individual animal weights. A weigh scale is used to ensure accurate dosage. A computer-based health system ensures that treatments follow veterinarian prescribed treatment protocols, and records all treatments. After treatment, the animal is usually marked with a specially formulated, non-toxic paint to ensure that everyone is aware the animal has been treated, and won’t be re-treated until needed. Drug selection is also carefully considered to ensure that there is a long enough withdrawal period before the animal leaves the feedlot. This is to ensure that no traces of antimicrobial substances remain with the animal before it is processed as a food product.

An enormous thank you to Mick Taylor and the staff at Cattleland Feedyards for opening their doors and showing our research team around their facilities, and for fact checking and contributing to this summary.

System Opportunities